5. The Socialist Labor Party (1876-1890)

|

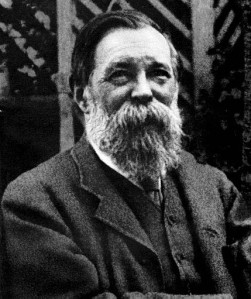

| Frederich Engels, along with Marx, was directly involved with the early development of the SLP in the US. |

dissolution of the International Workingmen's Association in 1876 to the

foundation of the Socialist Party in 1900, the Socialist Labor Party

was the standard bearer of Marxism in the United States. This marked the

next big stage in the pre-history of the Communist Party. The decades

of the S.L.P. were a period of intense industrialization, of growing

monopoly capitalism and imperialism, of sharpening class struggles, of

many of the greatest strikes in our national history, of big farmer

movements, and of the gradual consolidation of Marxism into an organized

force in the United States.

The need for a Marxist party being

imperative, the socialist forces proceeded to reorganize one in

Philadelphia, July 19-22, 1876, just a few days after the old I.W.A. was

dissolved in that same city. The new body was the Workingmen's Party of

America, the following year to be named the Socialist Labor Party. It

was based primarily upon a fusion of the Marxist elements of the I.W.A.,

headed by F. A. Sorge and Otto Weydemeyer, son of Joseph Weydemeyer,

and of the Lassallean forces of the Illinois Labor Party and the

Social-Democratic Party, led by Adolph Strasser, A. Gabriel, and P. J.

McGuire. All told, there were about 3,000 members represented. The

Philadelphia founding convention had been preceded by a unity conference

in Pittsburgh three months earlier.

The Lassalleans at the convention

succeeded in securing a majority of the national committee of the new

Party, and they also elected one of their number, Philip Van Patten, to

the post of national secretary. In the shaping of policy, however, the

influence of the Marxists was predominant. The Party demanded the

nationalization of railroads, telegraphs, and all means of

transportation, and it called for "all industrial enterprises to be

placed under the control of the government as fast as practicable and

operated by free co-operative trade unions for the good of the whole

people."1 The Declaration of Principles was taken from the general

statutes of the I.W.A., and in the vital matters of trade unionism and

political action, the Party's program unequivocally took the position of

the old International.2 That is, the new Party would energetically

support trade unionism and would base its parliamentary activity upon

substantial trade union backing. A program of immediate demands was also

adopted, and the Party headquarters was established in Chicago. J. P.

McDonnell became editor of the Party's English organ, The Labor

Standard, and Douai was made assistant editor of all Party publications.

Organizational, if not ideological, unity was thus established. The

conflicting Marxist and Lassallean groups went right on with their

disputes in the new organization. Lassallean opportunism, although as

such a declining force during the next decade, was soon to graduate into

its lineal political descendant, pseudo-Marxist right opportunism.

THE S.L.P. AND THE GREAT RAILROAD STRIKE

The economic crisis of 1873 was one of

the severest in American history. The employers, taking advantage of the

huge unemployment, slashed wages on all sides. The workers desperately

replied with a series of bitter strikes, such as this country had never

before experienced. These strikes were mainly spontaneous, most of the

unions having fallen to pieces during the economic crisis. In 1874-75,

there were broad, hard-fought strikes in the textile and mining

industries. The "long strike" of 1875 in the anthracite coal region of

Pennsylvania culminated in the hanging of ten Irish workers and the

imprisonment of twenty-four others, as "Molly Maguires." They were

falsely charged with murder, arson, and other violence against the mine

owners. This was another of the many shameful labor frame-up cases that

have disfigured American history.

The most important strike of this

period, however, was the big railroad strike of 1877. This reached the

intensity of virtual civil war. Beginning in Martinsburg, West Virginia,

on July 17, 1877, all crafts, Negro and white, struck against a deep

wage slash. Like a prairie fire the spontaneous strike spread over many

railroads, from coast to coast. The listing weak railroad brotherhoods,

led by conservatives, were but a small factor. For the first time the

United States found itself in the grip of a national strike.

The government proceeded ruthlessly to

break the strike. The big road centers were flooded with militia and

federal troops. About 100,000 soldiers were under arms.3 In many places

the soldiers fraternized the strikers; in others they fired upon the

crowds, and in some places the militant strikers drove them out. Many

scores were killed.

Finally, the desperate strike was

crushed. The workers learned at bitter cost the need for strong unions

and organized political action. This near-civil war deeply shook all

sections of the population throughout the land.

The Workingmen's Party was very active

in this great strike, as in all others of the period. The Party

executive urged the workers and the public to support the strike; it

raised the eight-hour demand and called for nationalization of the

railroads. In Chicago, a socialist stronghold, the Party organized an

effective general strike. "Chicago is in possession of the Communists,"

shrieked the newspapers. Albert R. Parsons was then one of the most

active Party leaders in Chicago. The leadership of the socialists in St.

Louis was also equally outstanding, and it made the strike very

effective. "This is a labor revolution," cried the local paper, The

Republican. For a week the Party-led strike committee was in virtual

possession of St. Louis.4 Finally, the strike was crushed by troops and

the wholesale arrest of the strikers' leaders. Activities were carried

on by the Party in other strike centers.

For the Workingmen's Party all this was a

new and tremendous experience in leading huge masses in struggle. It

was a powerful blow against the sectarian barriers that were separating

the Party from the workers. Marx and Engels hailed the great mass

struggle. In its 1877 convention the Party changed its name to the

Socialistic Labor Party of North America. The Party grew rapidly; by

1879 it had 10,000 members in 25 states, and between 1876 and 1878, 24

papers were established.

During this critical period, in 1877,

there was published in the United States the famous scientific work,

Ancient Society, by Lewis Henry Morgan. It was primarily a study of the

social organization of the Iroquois Indians and perhaps the most

important book ever written in the Western Hemisphere. Engels declared

that "it is one of the few epoch-making books of our times." Morgan was

not a Socialist, but Engels said of him that "in his own way [he]

discovered afresh in America the materialist conception of history

discovered by Marx forty years ago."5

WORKERS' AND FARMERS' POLITICAL STRUGGLES

Following the big strikes of 1877, the

workers, outraged by the brutal suppression methods of the government,

took a sharp turn toward political action. Labor parties sprang up in

many cities and states. In the meantime, the farmers, under the pressure

of the severe economic crisis, also embarked upon political activity.

They created the Greenback Party, whose cure-all panacea was the

issuance of paper-money green-backs, hopefully to pay off the farmers'

mortgages, to liquidate the national debt, and to finance a general

prosperity. In the 1876 elections the workers' parties refused to

support tire Greenback Party, because it had 110 labor demands in its

program.

By 1878, however, there had developed a

farmer-labor alliance, the National Greenback-Labor Party. This party,

which by then included in its program minimum labor demands, scored

considerable success in the elections of that year, polling its high

vote of 1,050,000 and sending 15 members to Congress. The capitalist

press shouted that the Communist revolution was at hand. But it was an

uneasy alliance of workers and farmers. Labor's forces resented the

domination of the party by businessmen and big farmers, and they also

reacted against the minor stress that was placed upon the workers'

demands. Disintegration of the party, therefore, set in; so that in the

1880 presidential elections its candidate, General Weaver, got only

300,000 votes. The Greenback-Labor Party was already far along the road

to oblivion.

The Marxists generally took a position

of participating in these important political struggles. They actively

supported the building of the local and state workingmen's parties, and

they also endorsed the general plan of a worker-farmer political

alliance. They raised demands, too, for the Negro workers. However, they

had opposed supporting the Greenback Party in the 1876 elections on the

sound ground that it did not defend the workers' interests. In the 1878

elections considerable socialist support was given to the

Greenback-Labor Party candidates, and in 1880 a national endorsement of

that party's candidates was extended by the Socialist Labor Party.

In the carrying out of this general line

there was gross opportunism. The Lassalleans, headed by Van Patten and

other middle class intellectuals, controlled the Party. Taking advantage

of the heavy defeats suffered by the trade unions during the economic

crisis and misinterpreting the swing of the workers toward political

action, they held that the trade unions had proved themselves to be

worthless and that thenceforth the Party should devote itself

exclusively to parliamentary political action. They elaborated upon this

opportunism by making impermissible compromises with the Greenbackers

and by surrendering to Denis Kearney of the Pacific Coast, with his

reactionary slogan, "The Chinese must go." They also watered down the

S.L.P. program until it called for the abolition of capitalism by a

step-at-a-time process. The Lassalleans, here and in Germany, were

gradually dropping Lassalle's original Utopian demand for state-financed

producers' co-operatives, and were being transformed into the

characteristic right-wing Social-Democrats, who were to wreak Such havoc

with the whole world's labor movement for many decades.

The crass opportunism of the S.L.P.

right-wing leadership antagonized Sorge, Parsons, Schilling, McDonnell,

and other Marxists and trade unionists in the Party. The latter

elements, in particular, insisted that the Party should combine economic

with political action. The Party conventions from 1877 to 1881 were

torn with quarrels over this issue. The factional split widened, minor

secession movements developed, membership declined, papers succumbed,

and the Party sank into an internal crisis. Meanwhile, a new danger

appeared on the horizon —anarcho-syndicalism. During the next few years,

this was to threaten the very life of the Socialist Labor Party.

THE ANARCHO-SYNDICALIST MOVEMENT

Anarcho-syndicalism originated from a

number of causes. Among these were the following: (a) the extreme

violence with which the government repressed strikes generated among

workers the idea of "meeting force with force"; (b) the robbing of

workers' election candidates of votes tended to discredit working class

political action altogether; (c) the fact that millions of immigrant

workers had no votes also operated against organized political action;

(d) the opportunist policies of the reformist leadership of the S.L.P.

disgusted and repelled militant workers; (e) the influence of

petty-bourgeois radicals upon the working class, and (f) the injection

of European anarchist ideas gave a specific ideological content to the

movement.

As early as 1875, to defend themselves,

German workers in Chicago formed an armed group. This tendency spread

rapidly, as a result of the government violence in the big 1877 strikes.

In 1878, the S.L.P. national executive condemned the trend and ordered

its advocates to leave the Party. In October 1881, the supporters of

"direct action," led principally by Albert R. Parsons6 and August Spies,

met in Chicago and organized the Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party.

This movement, however, did not take on a definitely anarchist

complexion until after the arrival of Johann Most, a German anarchist,

in 1882. Most found willing hearers, and in October 1883, a joint

convention of anarchists and members of the Revolutionary Socialist

Labor Party was held.

This convention formed the International

Working People's Association.7 Its program proposed "the destruction of

the existing class government by all means, i.e., by energetic,

implacable, revolutionary, and international action," and the

establishment of a system of industry based on "the free exchange of

equivalent products between the production organizations."8 The program

condemned the ballot as a device designed by the capitalists to fool the

workers. The Chicago group, more syndicalist than anarchist, inserted

the clause that "the International recognizes in the trade union the

embryonic group of the future society." Behind this movement was the

anarchist anti-Marxist conception that socialism could be brought about

by the desperate action of a small minority of the working class,

impelling the masses into action.

The opportunist-led S.L.P. shriveled in

the face of the strong drive of the anarcho-syndicalists. By 1883 the

S.L.P. membership had dwindled to but 1,500, whereas that of the

International went up to about 7,000. Also, the latter's several

journals were flourishing. In April 1883, after six years as S.L.P.

national secretary, Van Patten suddenly disappeared, turning up later as

a government job-holder. Shortly afterward attempts were made by

prominent S.L.P. members to fuse that organization with the

anarcho-syndicalist group; but to no avail, the latter replying that the

S.L.P. members should join their organization individually. From then

on it was an open struggle between the two parties.

The anarcho-syndicalist International

met shipwreck in May 1886, at Chicago. The militants of that

organization were taking a leading part m the A.F. of L. trade unions'

big agitation for the national eight-hour general strike movement, which

climaxed on May first. At the McCormick Harvester plant six striking

workers were killed by the police. The anarcho-syndicalists called a

mass meeting of protest in the Haymarket on May 4th, with Parsons,

Spies, and Fielden as the principal speakers. Some unknown person threw a

bomb, killing seven police and four rkers and wounding many more. In

the wild hysteria following this event, Parsons, Fischer, Lingg,

Fielden, Schwab, Spies, Engel, and Neebe were arrested. After a

criminally unfair trial, another on the growing list of labor frame-ups,

they were all convicted. Neebe, Schwab, and Fielden were glven long

prison terms; Lingg committed suicide while awaiting trial and Parsons,

Spies, Fischer and Engel were hanged on November 11, 1887. Governor

John Altgeld, six years later, released the four reining in prison and

proclaimed their innocence. Haymarket Affair was a heavy blow

especially to the International group and after a futile effort in l887

to amalgamate with the S.L.P it dissolved. The substance of the

Haymarket outrage was an attempt by the employers to destroy the young

trade union movement.

THE KNIGHTS OF LABOR

With the revival of industry, beginning

in 1879, trade unionism, weakened in the long economic crisis, again

spread with great rapidity. To meet the fierce exploitation by the

employers, the workers had to have organization. Local trades councils

and labor assemblies grew in many cities, and small craft unions also

began to take shape. The Socialists, while only a small minority in the

membership and leadership of the unions, were very active in all this

work. The S.L.P. Bulletin, in September 1880, declared that the

formation of the central bodies "has been accomplished mainly by the

efforts of Socialists who influence and in some places control these

assemblies, and are respected in all of them."9

A serious attempt to organize the labor

movement upon a national scale was made through the International Labor

Union, formed early in 1878. This center developed out of the joint

efforts of such Socialists as Sorge, McDonnell, and Otto Weydemeyer, and

also of the noted eight-hour day advocates, Ira Steward and G. E.

McNeill. The I.L.U. laid heavy stress upon the eight-hour day, and

advocated the ultimate emancipation of the working class. The

organization finally developed, however, chiefly as a union of textile

workers. It conducted a number of strikes, but was formally dissolved in

1887. More successful was the next big effort, the Knights of Labor.

The Noble Order of the Knights of Labor

was organized in Philadelphia in December 1869, by Uriah S. Stephens and

a handful of workers. It was at first limited to garment workers, but

in 1871 it expanded to other trades. With the decline of the National

Labor Union, the Knights of Labor grew and by 1877 it had 15 district or

state assemblies. Like various other labor unions of the period, the K.

of L. was a secret organization with an elaborate ritual. It held its

first general assembly, or national convention, in Reading,

Pennsylvania, in 1878, when it became an open body. The Order grew

rapidly in the aftermath of the great 1877 strikes and under the effects

of reviving industry. In 1883, the K. of L. had 52,000 members; in

1885, 111,000; and in 1886, its peak about 700,000. Stephens was its

Grand Master Workman until 1879-when he was succeeded by T. V. Powderly,

who served until 1893, at which time he was replaced by J. R.

Sovereign.

The K. of L. contained trends of

Marxism, Lassalleanism, and "pure and simple" trade unionism. Its

program set as its goal the Lassallean objective, "to establish

co-operative institutions such as will tend to supersede the wage system

by the introduction of a co-operative industrial system." It proposed a

legislative program which included labor, currency, and land reforms,

and also government ownership 0f the railroads and telegraphs, as well

as national control of banking. The Marxist influence was to be seen

chiefly in the many militant strikes of the K. of L. The Order

considered craft unionism too narrow in spirit and scope, and it aimed

at a broad organization of the whole working class. Its motto was "An

injury to one is the concern of all." The K. of L. accepted workers of

all crafts into its local mixed assemblies. It had many Negro workers in

its ranks and about 10 percent of its members were women. Professionals

and small businessmen were also admitted, to the extent of 25 percent

of the local membership.

Although its conservative leadership,

heavily influenced by Lassallean and outright bourgeois conceptions,

deprecated strikes, even sinking to the level of actual strikebreaking,

the K. of L. made its greatest progress as a result of economic

struggles. During 1884-85 the organization was especially effective in a

number of big strikes of telegraphers, miners, lumbermen, and

railroaders. Harassed masses of workers turned hopefully to the new

organization, and the employers viewed it with the gravest alarm. The K.

of L. swiftly became a powerful force in the industrial struggle. It

also was active politically, participating generally in the broad labor

and farmer political movements of its era.

The period of the rise of the K. of L.

was one of internal crisis within the S.L.P.—what with the crippling

effects of the right-wing leadership, the continuing pest of

sectarianism, and the severe struggle of the Party against the

anarcho-syndicalists. Nevertheless, the Party did exercise a

considerable influence in the K. of L. from its earliest period as an

open organization, particularly in the local assemblies, in various

cities where German immigrant workers were in force.

THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR

As the Knights of Labor developed, a

new, rival union movement, eventually to become the A.F. of L., also

began to take shape. This was based upon the national craft unions,

which could find no satisfactory place in the K. of L. These

organizations, some of which antedated the CiviL War, objected to the

mixed form of the K. of L., to its autocratic centralized leadership, to

its chief concern with other than direct trade union questions, and to

its neglect of their specific craft interests. Hence, gathering in

Pittsburgh, on November 15, 1881, six national craft unions painters,

carPenters, molders, glass workers, cigar makers, and iron, steel, and

tin workers—were the prime movers in setting up an organization more to

their liking, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the

United States and Canada.

Marxist influence was manifest but not

dominant in this new movement. Samuel Gompers, a Jewish immigrant cigar

maker born in London, who was its leading spirit, had long been

associated with Marxist circles; indeed, he had probably belonged to the

I.W.A., but later found it expedient to deny the fact. Gompers said

that he had studied German so as to be able to read Marx's Das Kapital.

Adolph Strasser, Ferdinand Laurrell, and P. J. McGuire, close Gompers

associates, had been members of the S.L.P. There were eight S.L.P.

members present among the 107 delegates at the founding convention.

Marxist conceptions also stood out in the new body's preamble, still in

effect in the A.F. of L. today. This signalizes "a struggle between

capital and labor, which must grow in intensity from year to year." The

constitution, which granted a high measure of autonomy to the national

unions, was copied almost verbatim from that of the British Trades Union

Congress and its Parliamentary Committee.10

The general trade union programs of the

K. of L. and the new Federation were similar, but there were also

important differences. "The Knights demanded government ownership of the

systems of transportation and communication, but the new Federation did

not. Nor did the Federation accept the monetary program of the Knights

of Labor, indicating that it definitely regarded the industrial

capitalist rather than the banker as the chief enemy of the

wage-earners, and-unlike the Knights—had pretty nearly rid itself of the

belief in financial panaceas. It is also significant that the

Federation made no reference to producers or consumers co-operatives,

and failed to recommend compulsory arbitration which the Knights

supported."11 The new Federation was evidently geared to limiting itself

to concessions under capitalism, rather than aiming at the abolition of

the existing regime of wage slavery.

It was clear soon after its foundation

that the new labor center, basing itself upon the skilled workers, was

little concerned with the welfare of the masses of semi-skilled and

unskilled. The A.F. of L. aimed chiefly at organizing the developing

labor aristocracy, a policy which dovetailed with the employer policy of

corrupting the skilled workers at the expense of the unskilled.' An

anti-Negro bias was also to H observed in the affiliated A.F. of L.

unions, reflecting the employers policy of discriminating against these

workers. These were long step backward from the National Labor Union and

the Knights of Labor. The K. of L. at its height, with some 700,000

members, had about 60,000 Negroes in its ranks, a figure not reached by

the A.F. of L. for about fifty years, when it counted, however, a total

of some three million members.

At first the new Federation was not

considered as an enemy of the Knights of Labor—thus, at its first

convention, 47 of the 107 delegates came from K. of L. organizations.

Potential antagonisms sharpened, however, and soon the two labor centers

were at loggerheads. Efforts were made, especially by the A.F. of L.

leaders in the early years, to harmonize and unite the two bodies, but

these came to naught and the rivals fought it out, to the eventual

disappearance of the Knights.

For its first five years the Federation

stagnated along, with only about 50,000 members. After its initial year

Gompers was its president. At the Federation's second convention, in

1882, only 19 delegates attended. Nor were the three succeeding annual

conventions any more promising. The attention of the workers, dazzled by

the successful strikes of the K. of L., was focused on that

organization. But the great events of 1886 were soon radically to change

the whole labor union situation.

THE NATIONAL EIGHT-HOUR FIGHT

The developing class struggle after the

Civil War reached a new height of militancy in the great fight for the

eight-hour day in 1886. The agitation for this measure had been on the

increase ever since the end of the war. Its foundation was the

intensified exploitation to which the workers were being subjected. Marx

called the eight-hour movement "the first fruit of the Civil War . . .

that ran with the seven leagued boots. . . from the Atlantic to the

Pacific."12

The Federation leaders, who were far

more militant then than now, seized upon the shorter-hours issue.

"Hovering on the brink of death, 'he Federation turned to the heroic

measure of a universal strike which had been suggested a decade before

by the Industrial Brotherhood. At its invention in Chicago in 1884 a

resolution was adopted to the effect that from and after May 1, 1886,

eight hours shall constitute a day's Work."13 The Federation put its

forces behind the movement, but Powderly, the head of the Knights of

Labor, a rank conservative, made the fatal mistake of opposing the

strike.

The general strike centered in Chicago,

where the Parsons-Schilling forces headed the Central Labor Union.

Nationally, it was highly successful, some 350,000 workers, including

large numbers of K. of L. members, going on strike. The eight-hour day

was established in many sections, particularly in the building trades.

And more important, despite the Haymarket outrage committed by the

bosses (described earlier), a tremendous wave of trade union

organization was set on its way. This laid the basis for the modern

trade union movement.

Out of this movement was born historic

International May Day, which, however, the A.F. of L., its creator, has

never seen fit to celebrate, although A.F. of L. unions participated in

May Day celebrations for many years. May first was adopted as the day of

celebration of world labor at the International Socialist Congress in

Paris, France, in July 1889. Since then, tens of millions of workers

have marched on that day in every city of the world, in anticipation of

the final victory of the

working class.14

The 1886 strike virtually decided that

the Federation and not the K. of L. would be the national trade union

center. At its December 1886 convention in Columbus, the original

Federation, now with some 316,469 members, and growing rapidly,

reorganized itself and adopted its new name of the American Federation

of Labor. Although the K. of L. gained heavily in numbers as a result of

the great 1886 struggle, it had definitely lost the leadership of labor

and soon thereafter began to decline in strength. By 1890 it had only

200,000 members and was no longer the decisive labor factor.

In the struggle for leadership the A.F.

of L. had a number of advantages over the K. of L. The craft form of

organization, based on the key role of the skilled workers in this

period, was superior to the hodgepodge mixed assemblies of the K. of L.

Its decentralized form was also more effective than the paralyzing

overcentralization of the K. of L. The A.F. of L.'s policy of confining

its membership strictly to workers likewise gave it a big advantage over

the K. of L., which took in large numbers of farmers, professionals,

and small businessmen. Its strike policy, too, was a big improvement

over the no-strike attitude of Powderly and his fellow bureaucrats. The

rejection of current money nostrums and other social panaceas that

infested the K. of L. also helped the A.F. of L., and so did the

opposition to the K. of L.'s adventurous petty-bourgeois political

policies.

Despite these advantages, which compared

favorably with the Knights of Labor, the A.F. of L. program contained a

whole series of weaknesses which were to manifest themselves with

deadly effect in the coming decades. The A.F. of L.'s gradual rejection

of a Socialist perspective implied its eventual outright acceptance of

capitalism and a slave role for the working class. Its concentration

upon the skilled workers finally developed into direct betrayal of the

unskilled and the foreign-born masses. Its obvious white chauvinism was a

callous sell-out of the Negro people from the start. Its opposition to

independent political action grew into a surrender to the fatal

two-party system of the capitalists. Its general program, which through

the years became a real adaptation of the labor movement to the profit

interests of the powerful and arrogant monopolists, finally resulted in

the wholesale corruption of the labor aristocracy, in the growth of a

monstrous system of inter-union scabbing, and eventually in the creation

of the most corrupt and reactionary labor leadership the world had ever

known.

In the early years of the A.F. of L. the

non-Marxist leadership of the unions, not yet solidly organized as a

dominating clique, reflected some of the militancy of the rank and file

under the latter's pressure. But with the development of American

imperialism, particularly from 1890 on, they soon fell into the role

allotted to them by the employers, as "labor lieutenants of capital,"

basing themselves upon the skilled at the expense of the unskilled. They

proceeded to build up the notorious Gompers machine, which ever since

has been such a barrier to working class progress. They were able to do

this because of the whole complex of specifically American factors,

related to the rapid growth of American industry, which had resulted in

relatively high living standards for the workers as compared to those in

other countries, and which were operating to prevent a rapid

radicalization of the American working class.

THE HENRY GEORGE CAMPAIGN

The great eight-hour struggle naturally

had important political repercussions for the workers. As the 1886 fall

elections approached, the workers organized labor parties in a number of

cities. The Socialists were active in all these parties, which played a

considerable role in the local Sections. But by far the most important

of such independent movements was the 1886 campaign of Henry George for

mayor of New York City.

Henry George, because of his notable

book on the single tax, Progress and Poverty, published in 1879 and

selling eventually up to several million copies, had gained a wide

popularity among the toiling masses. George considered the people's

woes as originating basically from the private monopolization of the

land, and his main social remedy was to tax this monopoly out of

existence. This was the single tax. George failed to note, however, as

Engels and the S.L.P. leaders sharply pointed out, that the main cause

of the workers' poverty and the antagonism of classes was the

capitalists' ownership of all the social means of production and that,

therefore, the final solution, as the Socialists proposed, could only be

had through the collective ownership by society of all these means of

production. George did not understand the capitalist class as the basic

enemy of the working class and the people. In his election platform,

however, he included demands for government ownership of the telegraph

and railroads, as well as some minor labor planks.

Henry George was nominated by the local

trade union movement in New York. The S.L.P. also endorsed his candidacy

as a struggle of labor against capital, "not because of his single tax

theory, but in spite of it." While basically criticizing the single tax,

Engels, who paid close attention to American labor developments, agreed

that the Socialists should offer Henry George qualified support. The

main thing, he said, was that the masses of workers were taking

important first steps in independent political action.

The bitterly contested local campaign

resulted in votes as follows: Abram S. Hewitt, 90,456; Henry George,

67,930; Theodore Roosevelt, 60,474. 15 The George forces claimed with

justification that they had been counted out. Following the New York

elections, the Socialists and the George forces split over the question

of program, and the single tax movement, torn with dissension, soon

petered out.

In the aftermath of the tremendous class

struggles, beginning with the big national railroad strike of 1877,

which climaxed in the eight-hour fight of 1886, the S.L.P., although

still weakened by internal confusion and dissension, began to grow. At

its seventh convention, in 1889, the Party claimed to have 70 sections,

as against 32 at its convention of two years before. The Party press was

also looking up-The Party, however, was far from having developed a

solid Marxist program and leadership. As yet, those who could actually

be called Marxists were very few. Consequently, the Party, while abiding

by its ultimate goal of socialism and using the writings of Marx and

Engels as its guide, was wafted hither and yon by the pressures of the

current class struggle. Still torn with division, the Party had, in its

fourteen years of life so far, developed various ideological deviations,

most of which were to plague the Socialist movement for years to come.

There were the "rights," who had

dominated the Party's leadership since its foundation in 1876. They

underestimated the importance of trade unionism, made opportunistic

deals with Greenbackers and other movements, yielded to Chinese

exclusionist sentiment, catered to the skilled workers, and generally

played down the leading role of the Party. Then there were the sectarian

"lefts," who wanted to cast aside the ballot as a delusion, refused to

participate in broad labor and farmer movements, toyed with dual

unionism, and satisfied themselves with mere propaganda of revolutionary

slogans. There were also the "direct actionists," anarcho-syndicalists

who, as we have just seen, had nearly wrecked the Party. And finally, on

the part of all these groupings, there was a deep misunderstanding and

neglect of the vital Negro question.

Marx, and especially Engels, gave direct

advice to the American Socialist movement during the seventies and

eighties, fighting against all the characteristic deviations.16 These

two great leaders sought tirelessly to break the isolation of the

Socialists from the broad masses, urging their active participation in

all the elementary movements of the working class and its allies—in the

trade unions, the labor parties, and the farmer movements. But the great

Marx died in 1883, and Engels followed him a dozen years later in 1895.

Thus the young American proletariat lost its two most brilliant and

devoted teachers and leaders.

One of the most serious handicaps of the

S.L.P. during this whole period was its almost exclusive German

composition. The publication of Lawrence Gronlund's Cooperative

Commonwealth in 1884, and Edward Bellamy's famous Looking Backward in

1888, helped to popularize Socialist and semi-Socialist ideas among the

American masses, but Justus Ebert could still say, "The Socialist Labor

Party of the eighties was a German party and its official language was

German. The American element was largely incidental."17 And Lawrence

Gronlund also said that m 1880 one could count the native-born

Socialists on one hand.

Engels spoke of the "German-American

Socialist Labor Party," and he fought to improve its isolated situation.

In a letter to Florence Kelley Wischnewetsky, he said of the S.L.P.:

"This Party is called on to play a very important part in the movement.

But in order to do so they will have to doff every remnant of their

foreign garb. They will have to become out and out American. They cannot

expect the Americans to come to them; they, the minority, and the

immigrants, must go to the Americans who are the vast majority and the

natives. And to do that, they must above all things learn English."18

In 1889, the internal dissensions within

the S.L.P. reached a breaking point. The opposition to the opportunist

leadership, according to Ebert, turned around three major points: "First

... its compromising political policy; second, its stronger pure and

simple trade union tendencies; third, its German spirit and forms."19

The revolt was led by the New York Volkszeitung (Schewitsch-Jonas

group), founded in 1878 as a German daily paper. The Busche-Rosenberg

official leaders of the Party, a hangover from the old opportunist Van

Patten group, were deposed and the Schewitsch-Jonas faction elected

instead. This led to a split, and in consequence for a while there were

two S.L.P.'s. The Rosenberg group, the minority faction, got the worst

of the struggle. It lingered along weakly, calling itself the Social

Democratic Federation, until finally it fused in 1897 with Debs' Social

Democracy. Lucien Sanial wrote the new program of the S.L.P. The split

strengthened the Marxist elements in the Party. The S.L.P. of today

dates its foundation from this period.

In the following year, 1890, an event of

major importance to the S.L.P. and the labor movement took place. This

was the entrance of Daniel De Leon into the Party. De Leon, born in 1852

on the island of Curacoa off the coast of Venezuela, was a professor of

international law at Columbia University, and had supported Henry

George in the 1886 campaign. Brilliant, energetic, and ruthless, De Leon

immediately became a power in the S.L.P. In 1891 he secured the post as

editor of the Weekly People (later a daily) which he held from then on.

For the next thirty years, long after his death in 1914, De Leon's

writings were to exert a profound influence not only upon the S.L.P.,

but upon the whole left wing, right down to the formation of the

Communist Party in 1919, and even beyond.

1 The Socialist, July 29, 1876.

2 Commons, History of Labor in the U.S., Vol. 2, p. 270.

3 Justus Ebert, American Industrial Evolution, p. 60, N. Y., 1907.

4 Hillquit, History of Socialism in the U.S., p. 233.

5 Frederick Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, p. 5" N. Y., 1942 (Preface to 1884 edition).

6 Parsons was nominated as the S.L.P.

candidate for president in 1879, but did not accept because he was too

young. See Lucy E. Parsons, Life of Albert R. Parsons, p-22, Chicago,

1889.

candidate for president in 1879, but did not accept because he was too

young. See Lucy E. Parsons, Life of Albert R. Parsons, p-22, Chicago,

1889.

7 Not to be confused with the International Workingmen's Association. See Chapter 4-

8 Hillquit, History of Socialism in the U.S., p. 238.

9 Cited by Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the U.S., p. 498.

10 Lewis L. Lorwin, The American Federation of Labor, p. 13, Washington, 1933.

11 Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US., pp. 523-24.

12 Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, p. 387.

13 Lorwin. The American Federation of Labor, p. 19.

14 For a fuller account, see Alexander Trachtenberg, History of May Day, N. Y., 1947.

15 Nathan Fine, Labor and Farmer Parties in the United States, p. 43. N. Y., 1928.

16 Most of Frederick Engels' writings on

the American question are to be found in the Preface to the American

edition of his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in

1844 (N. Y., 1887), and in many letters to Florence Kelley

Wischnewetsky. Sorge, and others. See Karl Marx and Frederick Engels,

Letters to Americans, New York, 1952.

16 Most of Frederick Engels' writings on

the American question are to be found in the Preface to the American

edition of his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in

1844 (N. Y., 1887), and in many letters to Florence Kelley

Wischnewetsky. Sorge, and others. See Karl Marx and Frederick Engels,

Letters to Americans, New York, 1952.

17 Ebert, American Industrial Evolution, pp. 66-67.

18 Engels, Preface to the American

edition of The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, p. v.

See Marx and Engels, Letters to Americans, Appendix.

19 Ebert, American Industrial Evolution, p. 66.

edition of The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, p. v.

See Marx and Engels, Letters to Americans, Appendix.

No comments:

Post a Comment